A Study into 21st Century Drone Acoustics

LP and Performance, 2015

Military drones fly at high altitudes and are often invisible to the human eye, it is only the sound of their propellers that reveals their existence. A sound that permeates everything, a frightening buzzing that seems to never stop. Those living under drones experience tremendous stress and anxiety from the sounds of drones. Together with composer Gonçalo F. Cardoso I investigated the sound of drones and how they have become a form of sonic violence.

Military drones fly at high altitudes and are often invisible to the human eye, it is only the sound of their propellers that reveals their existence. A sound that permeates everything, a frightening buzzing that seems to never stop. Those living under drones experience tremendous stress and anxiety from the sounds of drones. Together with composer Gonçalo F. Cardoso I investigated the sound of drones and how they have become a form of sonic violence.

The word drone comes from old English and is both the name for the male honeybee and the sound it produces. This buzzing sound or ‘drone’ is similar to engine noise, and it has become a synonym for unmanned aircraft. The border area between Afghanistan and Pakistan is where the sounds of military drones have been heard frequently. Drones are called bangana (بنګنه) for their eerie sound, which is Pashto for buzzing wasp. “They look at the sky to see if there are drones. The drones make such a noise that everyone is scared.” said an inhabitant of the region in the Stanford/NYU study ‘Living under drones’. The study has documented people’s experiences and reported cases of post traumatic stress syndrome as a result of the drone sounds.

Journalist David Rohde was held captive by the Taliban and describes what it is like living under drones. “The drones were terrifying. From the ground, it is impossible to determine who or what they are tracking as they circle overhead. The buzz of a distant propeller is a constant reminder of imminent death.” Over the city of Gaza the Israeli drones are nicknamed zanana (زنانة), which is a slang word for nagging wife, a word of which the sound imitates the propeller sound. Circling zananat are not just terrorising people with their buzzing, but also disrupt TV reception, invading Palestinian televisions.

Chainsaws and snowmobiles

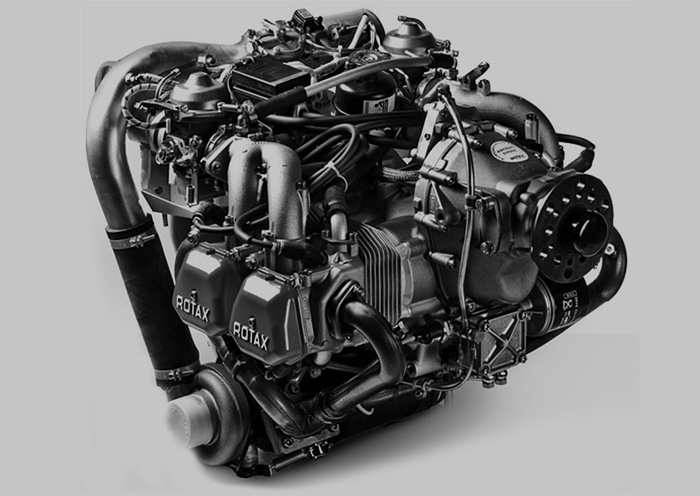

The sound that a drone produces depends on its size. Small commercial drones produce a high-pitched buzzing with their electric motors, usually four or eight. Smaller military drones are launched by hand or with a catapult, and are equipped with larger electric motors or small piston engines. The ScanEagle, a military surveillance drone used in more than twelve countries, has a two-stroke engine not unlike those used in a chainsaw or a weed trimmer.

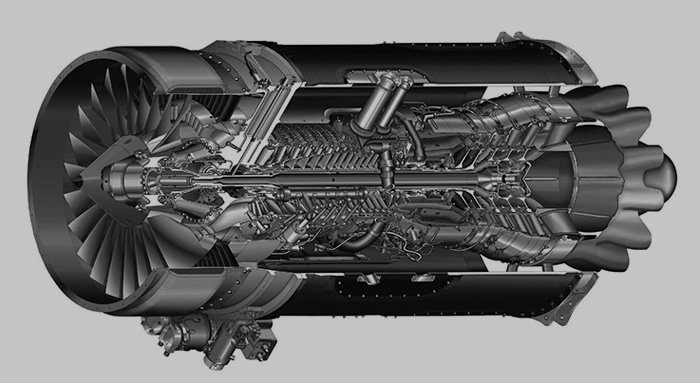

The Predator drone has the same four-stroke engine as a snowmobile. The Reaper drone is larger and has a turboprop engine like you would see in a small aircraft. The next generation of drones are equipped with jet engines, like the long range surveillance drone Global Hawk which can stay in the air for 34 hours. They are the largest types of drones and use engines like commercial aircraft or military jets, like the X-47B stealth drone which uses the same engine as the F-16. For the audio project ‘A Study Into 21st Century Drone Acoustics’ seventeen sounds of drones are collected, from small consumer drones to large long-range military drones. All are collected from online sources.

Death Metal

Sonic violence is not a new phenomenon. In ‘Sonic Warfare’, author Steve Goodman calls it ‘virtualized fear: ‘fear induced purely by sound effects, or at least the undecidability between an actual’ or ‘sonic attack’. In World War II the German Luftwaffe mounted sirens on the Ju-87 B-1 ‘stuka’ dive bomber. The horrifying, screeching sound was played during dive-bombing to strike the population with fear before the bombs would fall.

In 2005 the Israeli military used various methods of sonic warfare against the Palestinian population. ‘Sound bombs’ were deployed at night over Gaza; low-flying jets that break the sound barrier. Witnesses compared it to a large explosion, causing nose-bleeds, broken windows, and anxiety attacks. The Israeli army used special sonic weapons like the Long Range Acoustic Device (LRAD) as well. This ‘sound cannon’ was employed by city police against Occupy protesters in New York and recently in Ferguson, Missouri. Mounted on vehicles, it blasts a painfully loud siren in the direction it is pointed.

Music has been used as a weapon of torture at Guantánamo Bay prison. Metallica’s ‘Enter Sandman’ was played at extremely loud volume for hours on end, something that singer James Hetfield only applauded. He said “If the Iraqis aren't used to freedom, then I'm glad to be part of their exposure”. Using loud music in between interrogation sessions, it would take four days to ‘break’ someone, according to an interrogator.

Halo Hellfire

While the buzzing of drones is striking fear and terror, the drone operators are thousands of miles away without any audio feedback. Even the video feed is out of sync. Images taken with an infrared camera attached to the drone are transmitted by satellite with a two-to-five-second time lapse. Drone operators need to be immersed in sensory input for so-called situational awareness. Like playing a video game, their input is limited to a mediated representation. But gamers use surround sound speakers. Drone operators on the other hand, are less immersed. Their video feed is silent, abstracted, dehumanized. The absence of the sounds of war stands in stark contrast to the terror of the engine sounds over areas of conflict. The asymmetry of sound emphasizes how conflicts are increasingly fought far away, remotely controlled.

Side A of ‘A Study Into 21st Century Drone Acoustics’ carries the sounds of 17 drone types. Side B is a composition by Gonçalo F. Cardoso which delves into the acoustics of drones. His 23 minute soundscape is made with field recordings and ends with the song ‘Yalalela’ by Malinese singer Fadimoutou Wallet Inamoud. Her music comes from Azawad, a region where U.S. and European drones are currently deployed. The song is about love and nostalgia of the Tuareg, who seek an independent state.

On the nightly news, we can see the gaze of the aggressor when drone video feeds are shown. The people that are being watched are often not being heard. By sharing a song on the record, we hope to give a voice to those living under drones. Hopefully their voices will be amplified though music.

The LP is for sale at Discrepant records. The drone sounds can be downloaded for free on Soundcloud.

Concept by Gonçalo F. Cardoso & Ruben Pater. B side composition written and composed by Gonçalo F. Cardoso / Mastered & Cut by Rashad Becker at D&M, Berlin / Sleeve by Ruben Pater / Voice by Emmet O’Donnell / Song by Fadimoutou Wallet Inamoud courtesy of Sahel Sounds

Bibliography

Cavallaro, James, Stephan Sonnenberg, and Sarah Knuckey. Living Under Drones: Death, Injury and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan. Stanford Law School; New York: NYU School of Law, Global Justice Clinic, 2012.

Goodman, Steve. Sonic Warfare. London: MIT Press, 2010.

Gregory, Derek. “Drone Geographies,” Radical Philosophy 183, Jan/Feb 2014.

Hass, Amira. “In Gaza, a Hamas informer and a UAV have just one name,” Haaretz, July 28, 2015.

Hussain, Nasser. “The Sound of Terror: Phenomenology of a Drone Strike,” Boston Review, October 16, 2013.

James, Robin. “Drones, Sound, and Super-Panoptic Surveillance,” The Society Pages, University of Minnesota, October 26, 2013.

Smith, Clive Stafford. “Welcome to ‘the disco’”. The Guardian, June 18, 2008.

Sorcher, Sara. “In Pakistan, Drones Have Made Their Way Into Love Poems,” National Journal, May 12, 2014.

Wilson, Kevin A. “UAVs Graduate Beyond Lawnmower Engines,” Popular Mechanics, June 8, 2010.